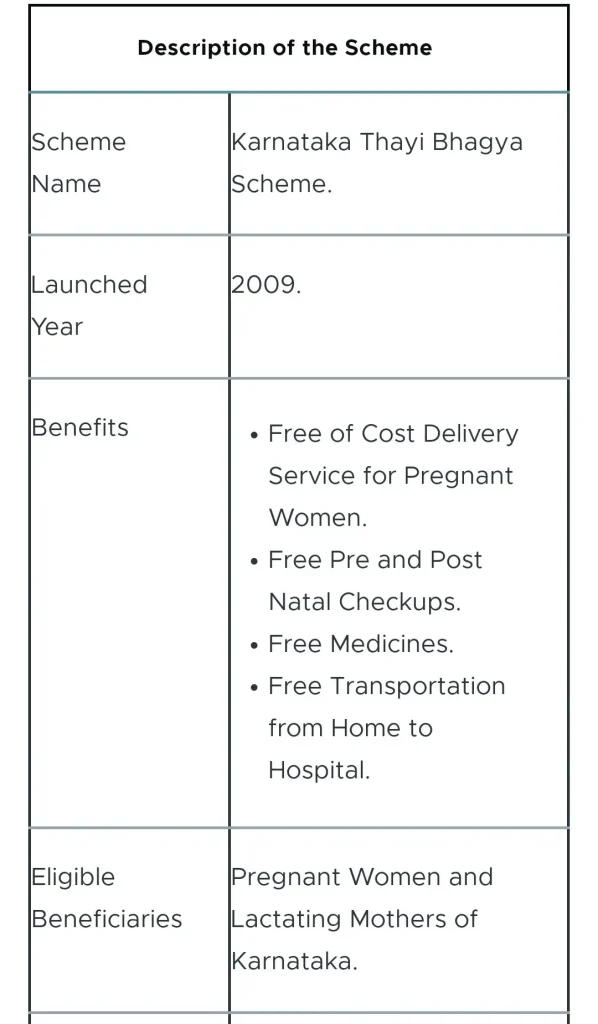

The Thayi Bhagya Scheme, Karnataka’s maternal-health programme offering free delivery and prenatal services to vulnerable women, continues to influence access to safe childbirth across the state. Introduced in 2009, it targets Below Poverty Line (BPL) and Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe (SC/ST) families and aims to reduce maternal and neonatal health risks by enabling institutional births.

Understanding the Thayi Bhagya Scheme

Launched by Karnataka’s Department of Women and Child Development along with the Department of Health and Family Welfare, the Thayi Bhagya Scheme was created to support pregnant women who lacked access to trained medical care. The state adopted a hybrid model that allows both government hospitals and empanelled private hospitals to offer cashless services for maternity care.

The idea for the scheme emerged after policymakers observed persistent shortages of specialists in public hospitals, particularly in rural and low-resource districts. Many government facilities lacked gynaecologists, anaesthetists, and paediatricians, while private hospitals had specialists but remained unaffordable for poor families. Thayi Bhagya addressed this gap by reimbursing private hospitals for treating eligible mothers.

Objectives of the Thayi Bhagya Scheme 2025

The scheme was designed with several clear goals:

- Increase institutional deliveries to reduce maternal and infant mortality.

- Provide equitable maternal healthcare to marginalised communities.

- Strengthen antenatal monitoring and early detection of high-risk pregnancies.

- Reduce out-of-pocket expenditure for vulnerable families.

- Leverage private hospitals’ capacities through public–private partnerships.

Public-health experts note that such schemes, when implemented well, have significantly improved access to safe maternal care in developing regions.

Eligibility Criteria for Thayi Bhagya Scheme 2025

To receive the benefits, pregnant or lactating women must:

- Be residents of Karnataka.

- Belong to BPL, SC, or ST communities.

- Be registered for antenatal care with local health workers.

- Typically be within the first two live births.

Registration usually takes place through Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs), or Junior Female Health Officers. These workers help verify documents, coordinate antenatal visits, and guide the woman to a hospital during delivery.

Benefits Offered Under Thayi Bhagya Scheme 2025

The Thayi Bhagya Scheme covers a wide range of maternal-health services at no cost to the beneficiary.

Free Institutional Delivery

Eligible women can deliver in government or empanelled private hospitals without paying admission or delivery charges. The scheme covers normal deliveries, Caesarean sections, and emergency obstetric care.

Cashless Antenatal and Postnatal Care

The scheme ensures routine check-ups, prescribed medicines, laboratory tests, ultrasound scans (as per guidelines), and postnatal follow-up visits.

Transport Assistance

Transport support helps pregnant women reach the hospital during labour, addressing a major delay that often leads to complications.

Financial Support Through Thayi Bhagya Plus

If a woman delivers in a private hospital outside the list of empanelled facilities, she may receive ₹1,000 under the Thayi Bhagya Plus component, depending on eligibility.

Reimbursement Model for Hospitals

The reimbursement structure is straightforward:

- Private empanelled hospitals receive ₹3,000 per delivery.

- Government hospitals receive ₹1,500 per delivery.

This ensures predictable expenditure for the state. However, private hospitals have expressed concerns that the reimbursement does not fully cover operational costs, particularly for Caesarean deliveries or cases requiring prolonged care. This has affected empanelment in some regions.

Historical Trends and Impact

In districts where implementation was strong, researchers observed notable improvements:

- Institutional deliveries increased by 30 to 37 percent in the early years of implementation.

- Home births decreased, especially in tribal and remote areas.

- Early identification of high-risk pregnancies improved due to regular ANC visits.

These changes contributed to Karnataka’s reduction in maternal mortality over the last decade. However, experts caution that improvements result from a combination of state and national programmes, so the impact cannot be attributed to Thayi Bhagya alone.

Ground-Level Implementation

Successes

- Strong adoption in districts such as Bagalkot and Vijayapura where ASHA networks are active.

- Increased medical supervision that helps identify complications like anaemia and hypertension.

- Better newborn care linkages, with more mothers accessing immunisation and nutritional support.

Challenges

- Uneven implementation between districts due to varying awareness levels and empanelment rates.

- Low reimbursement amounts discourage some private hospitals from participating.

- Documentation challenges for migrant workers, nomadic tribes, and unregistered labour families.

- Transport difficulties in remote rural regions despite the scheme’s provision.

- Limited monitoring of care quality in private facilities.

Public-health officials have emphasised the need to strengthen administrative oversight and enhance awareness campaigns to address these gaps.

Comparison With Other Maternal-Health Schemes

India has multiple maternal-health programmes, some of which overlap with Thayi Bhagya.

Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY)

A national scheme offering cash incentives for institutional deliveries among BPL families.

Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY)

Provides up to ₹5,000 for the first living child to support nutrition and pregnancy-related expenses.

Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK)

Ensures free delivery, Caesarean sections, medicines, diagnostics, and newborn care in public hospitals.

How Thayi Bhagya Differs

Thayi Bhagya is unique to Karnataka and focuses specifically on SC/ST and BPL families. Its strong reliance on private hospitals through a public–private partnership model distinguishes it from other schemes.

Funding and Administration

The scheme is funded through Karnataka’s health and family welfare budget. Funds are distributed to districts for:

- Hospital reimbursements

- ASHA worker training

- Diagnostics and medicines

- Awareness programmes

District Health Officers (DHOs) and Taluk Health Officers (THOs) supervise implementation. ASHA workers play a crucial role in mobilisation and follow-up.

Women to Get Biggest Electric Scooter Subsidy in 2025 — Up to ₹46,000 Benefit

Expert Perspectives and Field Experiences

A senior obstetrician at a government district hospital said:

“Schemes like Thayi Bhagya remove financial barriers for the poorest women. We see more high-risk mothers coming on time because the cost factor is eliminated.”

A District Health Officer in northern Karnataka added:

“Our focus is on ensuring every pregnant woman receives the Thayi Card early in pregnancy. Early registration allows us to track complications and guide them to safe deliveries.”

ASHA workers in tribal regions report significant behavioural changes:

“Earlier, many women feared hospital costs and delivered at home. Now, they trust that the delivery is free, and we help arrange transport,” said an ASHA supervisor working near the Karnataka–Maharashtra border.

Digital Integration and Future Improvements

The Karnataka Health Department is exploring digital tools for:

- Tracking antenatal registrations

- Monitoring high-risk pregnancies

- Recording referrals and outcomes

- Improving accountability across districts

The Thayi Card, encouraged for universal early issuance, plays an important role in digital integration and consistent maternal-health tracking.

Conclusion

The Thayi Bhagya Scheme remains a central part of Karnataka’s maternal-health strategy. By providing free delivery services, antenatal and postnatal care, and transport support to BPL and SC/ST women, the scheme continues to promote institutional births and reduce health risks.

However, challenges such as uneven district-level implementation, low reimbursement amounts, documentation difficulties, and transport barriers must be addressed for the scheme to reach its full potential. Strengthening awareness programmes, expanding hospital participation, improving monitoring, and increasing support for high-risk groups will help Karnataka advance toward safer maternal and child health outcomes.